Last night, in an attempt at a comeback, the Hollywood Foreign Press and the Golden Globes hired a Black host, made sure there were plenty of Black presenters, gave 5 of their 27 awards to Black artists, and had their president tell us about the journey they’re on to bring “representation” to their organization. Then they proceeded to give out the 2 biggest awards of the night to categories in which there were no Black nominees.

That’s Hollywood for you.

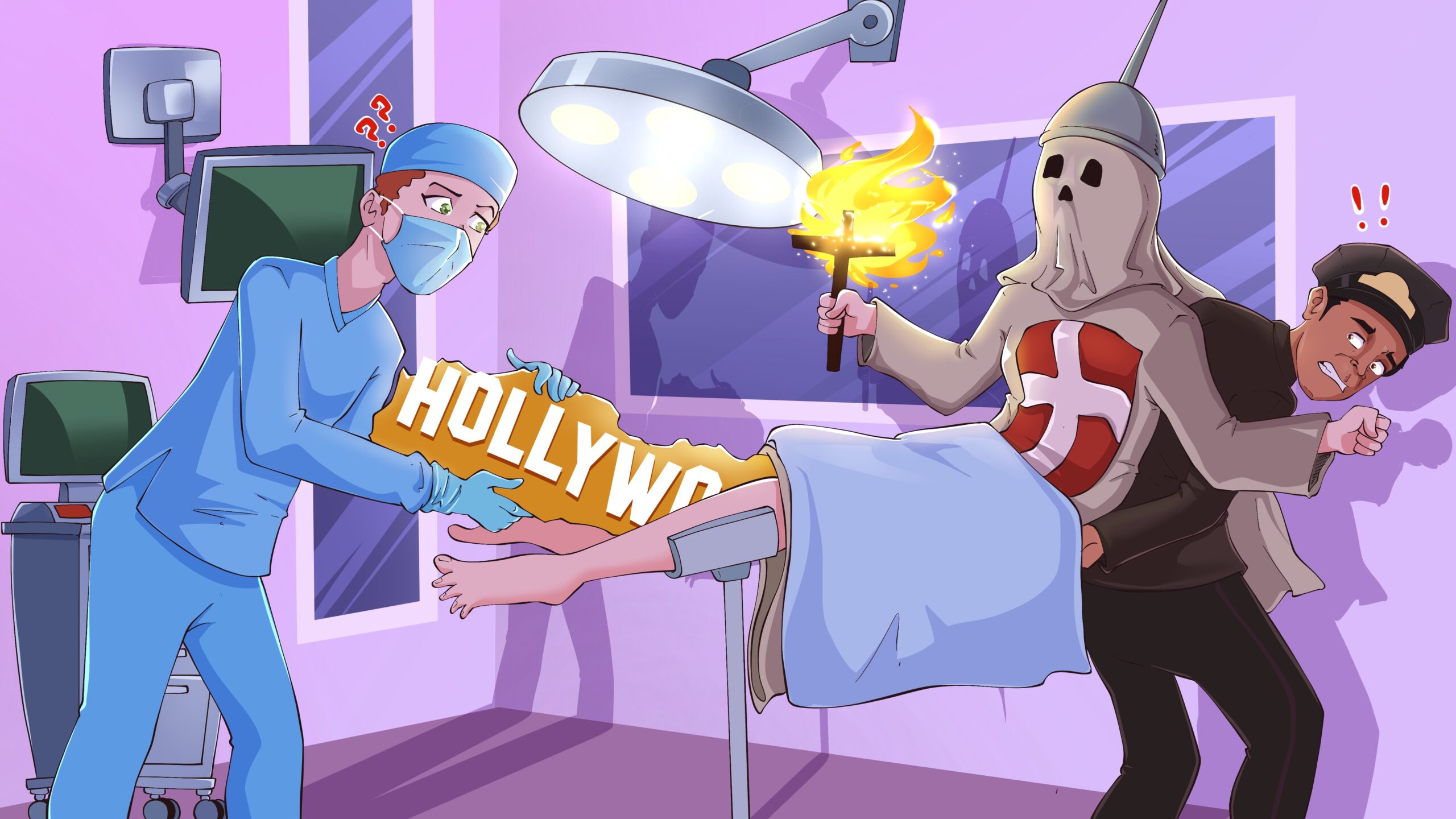

But the ills of Hollywood were obviously started long ago. In fact, many historians mark its beginning with the debut of “Birth of a Nation.”

People often look at “Birth of a Nation”–the notorious 1915 silent film chronicling Reconstruction through the celebration of the Ku Klux Klan and pro-Confederacy beliefs–as an ugly depiction of America and its sentiments toward Black people. It has been called “the most reprehensibly racist film in Hollywood history.” And it was.

But it was much more.

To the general public alone, the story of how this movie came to be is the perfect American story–a tale of the mainstream man putting it all on the line for a vision they believed in, triumphing against all odds, and proving their doubters wrong.

And to the industry from which this movie belongs, “Birth of a Nation” is the perfect embodiment of everything the entertainment industry would soon become. As this wasn’t just a movie that glorified the dehumanization of Black people, but in the making of “Birth of a Nation”, a movie many historians label as the very genesis for what we now call Hollywood, was a plantation-like delegitimization, humiliation, and profiteering off of Black people and their images that culminated in becoming what I believe to be Hollywood’s Original Sin.

Relatively few people disagree with the notion that the depiction of Black people in this movie was disgusting. But to stop there is to not go far enough into a past that has led us directly to the troubles of the present, because what has gone on in Hollywood for over a century is about more than stereotypes.

Today, we go deeper than that. Today, we talk about how an industry’s more than century’s worth of intentional misrepresentation, degradation, and wealth destruction toward an entire race has stood the test of time and continues to plight Black people as we speak.

Misrepresentation

You don’t have to spend a semester or two a sociology class at a liberal arts school to call out how poorly Black people have been portrayed by the media. At the practice’s genesis, it all started with the movie industry denying Black people roles in film because Black people weren’t considered worthy of the profession and were antithetical to a race-based marketplace. But after decades of exclusion, Black people finally began to get acting opportunities in the 1920s, when they were asked to play stereotypical “Toms”, coons and Mammy’s on screen. As skewed and misrepresentative as those opportunities were, early Black actors and actresses in Hollywood took these roles on anyway, carrying a burden Black people still have to shoulder today, which is that Black people often have to take these hurtful, demeaning, first steps forward so that those that come after them can walk an easier path.

Black misrepresentation in media didn’t magically stop sometime in the 1920’s, 40’s, 60’s, or 90’s. No, racism is still here with us in modern media. In 2015, with 20 actors and actresses nominated for the key acting Oscars at the 87th Academy Awards, all 20 of the nominees were white. This happened again and immediately in 2016. In 2020, at the 92nd Academy Awards, just 1 non-white person, Cynthia Erivo, was nominated for a top acting award. After George Floyd’s death, the 2021 Oscars had 9 Black actors nominated, but with the distance of an additional year of time, the 2022 Oscars yielded just 4 Oscar nominations for Black actors.

Degradation

As for the historical degradation of Black people in Hollywood, it’s hard to pick a place to begin. I guess I should’ve noted earlier that pre-dating Black people getting roles in Hollywood, the industry simply said, instead of hiring Black people, why don’t we just let white people put black makeup on?

Blackface was used to kill two birds with one stone: profit off of caricatures of Black people, while suppressing any real images of Black people on the screen. And when Black people finally did make it on screen, even before the aforementioned stereotypical roles, it was the song and dance shows, like “Amos and Andy”, that came calling. But should a negro dare rise above it all, showcasing talent that exceeded the expectations of blackface, song-and-dance, and so-called Tragic Mulatto roles, the industry still relegated Black actors to “less than” status.

Case and point: 1940. Hattie McDaniel.

That year, McDaniel was nominated for and won the Oscar in the Best Supporting Actress category, the first acting Oscar ever awarded to a Black person. However, she was still asked to sit at a different table from her white castmates and away from Hollywood’s elite. This was essentially the industry saying “fuck you” to a person they themselves deemed among the best of the best at acting, merely because she was Black.

While today, Black people do not have to walk in McDaniel’s exact shoes, acts of degradation still take place. Take something as simple as how Black men have complained about the treatment of their hair on sets. It seems benign, and relatively speaking, it is. But it really does put you in your place when you are the star of a movie, TV show, or special, and your white male counterpart gets the best hairstylist in Los Angeles, while prominent Black actors often complain about having people who have never worked on Black hair assigned to take care of theirs.

Wealth Destruction

As if misrepresenting and degrading Black people weren’t enough, Hollywood had to take our money too. When it comes to some of Hollywood’s historic methods of wealth destruction, let’s take it back to the birth of the blaxploitation genre in 1971, when “Shaft”, starring Black actor Richard Roundtree, was released.

It is reported that the movie cost just $700,000 to make and raked in over $16 million, and that’s not including anything beyond the theatrical release. Not only was this wildly successful for any genre in the 1970’s, but the movie is believed to have saved its studio, MGM, from bankruptcy, because it was so unfathomably profitable. And for his starring role as Shaft, in a studio-saving production, Roundtree was paid a paltry $13,500. But you might say, “Well, that was an example of a movie that was the first of its kind, way exceeded expectations, and the studio reaped the rewards for taking the risk!”

Okay.

Maybe.

But the right thing to do would be to pay him fairly if they did a sequel, right?

Wrong!

They paid him just $50,000 for the sequel. And that amount is about more than whether Roundtree got paid fairly–it’s about wealth destruction across the entire Black economy.

Despite the fact that blaxploitation movies were almost exclusively being shown in Black neighborhoods, showcasing Black celebrities, and co-opting the Black power movement for financial gain, Hollywood studios took those blaxploitation dollars out of Black neighborhoods, underpaid their star Black actors, and built up their own coffers, which they used to propagandized police brutality against Black people in other movies and on TV. In fact, MGM, which was saved by blaxploitation movies and Black viewers, would go on to produce 298 episodes of “Live PD”, a show that often glorified the use of force by police, making untold millions off programming that over-indexed on the brutal chasing down of Black men. Just think of the wealth that could’ve been created in Black communities had those dollars been recirculated among the actors, civil rights groups, and small Black businesses that made those Blaxploitation movies possible. Instead, those very same funds were used against them.

But when it comes to wealth destruction, there is no bigger harm than what Hollywood has done to Black women. They have been underpaid since the dawn of Hollywood, and it persists to this very day. Obviously, every industry, not just Hollywood, has found a way to systemically underpay Black women, as they get paid a mere 63 cents on the dollar for every dollar paid to a non-Hispanic white man. However, unlike Hollywood, most industries don’t lay claim to being this beacon of fairness, liberalness, and equality, while then paying Black women less than their counterparts. In 2020, on the list of the top 10 highest-paid actresses, Viola Davis, was the lone Black woman. In 2019, there were no Black women on the list. In 2018, it was also 0. In 2017, it was 0 again. You get the point.

If you don’t, then I’ll refer you to Octavia Spencer, a Black actress, who when talking about salaries for her movie “The Help”, found out she was making five times less than her co-star, Jessica Chastain, a white actress. Notably, Spencer is the more decorated actress, has a competitive Q Score, and would go on to actually beat out Chastain for the Supporting Actress Oscar for her role in the very movie in which she got paid less to work on than Chastain.

Whereas one might think the democratization of the internet might have solved some of these ills, they haven’t. In fact, they may have even exacerbated them. YouTube, for example, has long had issues with Black creators feeling as if they’re not receiving proportional viewership, monetization, or even manual promotion by YouTube itself. More recently, Black users of TikTok have complained about having their videos shadowbanned, their work appropriated, and advertisers paying them far less on a per-follower basis.

For followers of Hollywood and the media, these anecdotes of misrepresentation, degradation, and wealth destruction are of no news to you. But how these problems began, and continue, to exist for Black people just may be.

Birth of a Nation and the Birth of the Blockbuster Film

“Birth of a Nation” created Hollywood as we know it. While much of the focus on this movie’s immense historical importance is centered around its promotion of racism and the social dialogue and civil protests it inspired, the more Hollywood-esque plot lies not in the story’s plot line, but in the development of it.

The movie is an adaptation of a novel by Thomas Dixon, a noted white supremacist, who actually had a 1911 version of “Birth of a Nation” produced but with next to little fanfare. After the failure of that movie, Dixon still had faith that there was a theatrical audience for his project, as it had tremendous success as a stageplay and he believed it would translate well as a film if given adequate backing. But the stench of failure with his earlier version, coupled with the fact that the story depicted too many war scenes to fit within the realm of a normal movie budget, resulted in the film getting rejected by every studio in the business.

Eventually, Dixon would go on to meet film producer and director D. W. Griffith, another historically noted white supremacist, who decided to option the movie from Dixon. But it turns out, when it came time to option the movie, Griffith could only pay a small fraction of the option amount he had promised. Instead of backing out of the deal, Dixon decided to take a huge risk and accepted a 25% stake in the movie, betting both on his story and against the negative backlash that the release of the movie was sure to face.

Griffith secured $40,000 in funds to produce this movie, which involved the use of West Point engineers, several war scenes, never-before-used camera techniques, slave ships, an original music score, and lots of Blackface to account for all the racism and lack of principal Black actors–you know, because it was 1914.

With all of those necessary elements, the movie’s budget would soar to over $100,000, which is more than $2.5 million in today’s dollars, which made it the most expensive movie ever as of its release. That massive budget, put together with the film’s attention to detail, innovative techniques, and outsized marketing campaign made it into what can best be described as Hollywood’s first attempt at a mega-blockbuster film. But the movie wouldn’t get to attempt blockbuster status without challenges.

In particular, the NAACP attempted to get the film banned and worked with local governments to do so. But a clever White House screening of the movie, the first movie to ever be screened by a President there, helped spurn the NAACP’s efforts, securing an effective and wide movie release for “Birth of A Nation”.

The movie would go on to make over $50 million dollars at the box office, which was a 500x return on their production budget, and would be the equivalent of a $1.25 billion box office movie in today’s dollars. A 500x return on a movie is like investing in Google–that’s just not supposed to happen with a film.

The success proved Dixon’s vision right, and the big risk he took in accepting a 25% stake in lieu of cash made him a very rich man, all because he took the risk and was willing to bet on himself and his vision.

It was that risk and the resulting success of a small group of white men, profiting off of a racist movie, that cemented the public’s desire and the financial future of movies in America. This was the movie industry’s first blockbuster hit, and as movie historian Lee Pfeiffer put it, “[Birth of Nation] secured both the future of feature-length films and the reception of film as a serious medium”.

Essentially what he’s saying, and I’m paraphrasing: this racist movie birthed Hollywood.

Racist TV Evolves into Black TV

Perhaps it was no coincidence, that soon after “Birth of A Nation’s” success, racist propaganda, Blackface, and stereotypical Black characters began to grow in terms of their frequency in movies, as well as in the burgeoning radio and TV industries of the 1920s. This led to some of the aforementioned song-and-dance shows. Thankfully, the NAACP protested many of these shows, leading to their eventual demise.

Still, it wouldn’t be until the 1960’s when Black people would get an actual fair shot at a place on television, which had by then, established itself as the medium of the typical American household. In that decade, inspired by the rise of Bill Cosby and the Civil Rights Movement, the television industry vowed to be more inclusive, as the National Broadcast Editorial Conference of 1964 came out in support of more inclusive television on the airwaves. And believe it or not, Hollywood acted on the moment, and by the decade’s end, there were 19 Black shows on the air!

However, as the Civil Rights movement faded after the death of Martin Luther King Jr., President Nixon’s rising political issues, and the rise in anti-Vietnam War protests, Hollywood’s interest in Black television faded too. By the end of 1971, there was just 1 Black show on TV.

In the mid ’70s, the aforementioned popularity of blaxploitation films did bring about some experimentation in Black TV shows. But like the films this experimentation arose from, many of these new Black shows primarily depicted Black people living in stereotypical settings and situations.

It wouldn’t be until the mid ’80s and ‘90s when Black people got another legitimate chance to get on screen. Cosby’s return to television with NBC’s “The Cosby Show” proved that a Black show could become and sustain a leadership position in America’s homes. NBC would go on to have additional success with “A Different World”. And with the rise of cable television in the 80s, including a new Black-owned channel dubbed Black Entertainment Television (BET), Black TV was beginning to get really profitable.

Rupert Murdoch, having recently bought Fox, decided to replicate NBC’s success with Black programming in an attempt to bring Fox out of a distant fourth place in the ratings. And it worked. Because of early 90’s favorites like “Martin” and “In Living Color”, Fox vaulted into competitive status with the other 3 broadcast networks.

As Hollywood invested more in TV throughout the 90s, Black people were indeed beneficiaries of some of the growth. Some of the amazing Black showrunners of today, like Mara Brock Akil and Kenya Barris, got their start working on Black shows during this era. Speaking of sitcoms alone, there were 15 of them at the Black TV peak of 1997. And the shows weren’t song-and-dance programs or 30-minute blaxploitation sitcoms either. Most of them involved Black creators and writers who wanted to show the untold parts of Black life in America. And they got to. At least for a while.

All Good Things…

Just like with the end of the 1960s, the 90’s impressive run of Black representation on TV faded by 2001. Whereas in the 60s/70s it was due to fading interest from Hollywood in aligning themselves with the Civil Rights Movement, this time, it was simply a money grab. Off the backs of Black programming and Black audiences, not only did Fox begin to compete in the 1990s ratings wars, but the brand lift helped Fox score a deal to bring NFL programming to Fox–which ultimately cemented Fox as a major American media company. As we all know, Murdoch then used that clout to build one of the most racially slanted news networks of our times.

And like Murdoch with Fox, the other networks also noticed how increased interest and viewership from Black viewers could be leveraged into building a broader, less Black, audience. So NBC, Fox, UPN, and the WB all took incredible pivots away from Black shows and towards shows with predominantly white casts. NBC prematurely canceled “A Different World” and ran with “Friends”. Fox moved away from shows like “Living Single” and into shows like “That 70s Show”. And the WB pivoted away from its focus on Black content entirely, opting for a teen-centric network instead.

With this mass exodus from Black programming, both in the 60s and the 90s, why was it that the same people, white male executives, determined when and how Black people could appear on television?

It’s a simple answer: ownership.

How Black Ownership in Media Was Systemically Prevented

The success of “Birth of a Nation” taught Hollywood at least two things. First, executives realized the power they possessed in telling stories that could ignite passions and form opinions–like racism.

Second, the enormous payday for Dixon was a big lesson on maintaining ownership of those stories, as having the right amount of equity in the outsized results from an unexpected cultural hit could be the difference between getting a nice bonus check and wealth for decades to come. With the realization of how valuable ownership is in the telling of stories, and the fact that the government has long supported laws and regulations that hinder Black advancement, it comes as no surprise that the government suppressed Black and minority ownership in media for decades–and continues to do so today.

How the Government Stifled Black Media Ownership

There is clear documentation of the FCC refusing to grant radio station licenses to Black people, handing out licenses to segregationists, and requiring overly stringent financial qualifications in order to keep Black people out of the running for future licenses. Despite the fact that in 1950 there was enough ability for minorities to own over 3,000 of the nation’s newspapers, which were not regulated by a governing body, minorities owned 0 radio stations, which were fully governed by the FCC. The government’s blocking of Black-owned radio stations not only prevented them from prospering as owners of radio, but perhaps more importantly, it prevented them from being well-positioned to make the transition into TV ownership, just as NBC and CBS did when TV began to take over. As a result, minorities own just 2.6% of TV stations and just 1% of all asset value in the TV industry.

Another clear example of costly government bias is that for 23 years, from 1984 to 2007, minority broadcasters lost $200m per year in lost advertising revenues due to “no urban” and “no Spanish” edicts made by advertisers. Despite being fully aware of these practices, the FCC allowed this practice to persists for 2 decades, until finally banning it. However, there is little to no enforcement of this rule, which is why so many advertisers were called out in 2020 for the woefully paltry number of dollars they were investing in Black media companies.

And the entertainment industry’s old guard continues to make things hard for Black people in present day. Recently, Byron Allen, a Black media businessman, and his company, Entertainment Studios, were embroiled in a legal battle with Comcast. In the case, which went from 2015 to 2020, Entertainment Studios claimed that Comcast’s refusal to include Allen’s cable channels in Comcast’s lineup was being done on the basis of race. How did Allen plan to prove that? Well, one thing he did point out was that only $3 million of the $11 billion that Comcast pays out in carriage fees were paid to 100% minority-owned networks. Ultimately, the courts didn’t go for that argument, nor the rest of Allen’s case, and Comcast won. However, the two sides did settle after Entertainment Studios appealed the ruling.

I bring up the case against Comcast not to ascertain whether they were racist or not. I bring it up to recognize the power that it, a company run by the white male heir to the original founder, has over a Black company trying to build a media company in the 21st century. Allen needed to convince this behemoth of a cable company to provide him distribution, and if they didn’t want to, for any reason, his entire cable channel business was essentially going to be rendered worthless.

That Said, We Don’t Always Take the Risks

The systemic racism that persists in America is undoubtedly the primary reason Black people don’t have their fair share of ownership and success in the media industry. But with that as a given, if we are to come out of it, then we are going to have to create and build our own media companies, from the ground up. Not unlike Thomas Dixon did with “Birth of A Nation”, forging your own path requires taking risks.

Unfortunately, our socioeconomic status in this country is a huge deterrent to taking risks. It’s reasonable to come to the conclusion that if you’re among the few Black people that get the education, opportunity and backing to be an entrepreneur, there are probably so many other things you can excel at that don’t require taking that professional and financial risk of starting your own business. Often, you will hear Black college graduates talk about how they had to take careers in medicine, law, engineering, or finance because there’s no way they could justify “blowing” their parents’ hard work on a career where there was no guaranteed outcome of prosperity.

Of course, one might think that last sentiment goes gainst the very fact that Black people start businesses at higher rates than other racial groups. However, because Black people systemically have higher unemployment rates than white people, the turn to entrepreneurship may not always be a choice, but also a realization of the fact that relying on an employer may not be the most reliable path for Black individuals who want to achieve greateness.

Case and point, Tyler Perry. This is a man of incredible skill and talent who at every turn (after he worked his ass off and up!) was offered the chance to take more money and cede ownership of the films and TV shows he was creating. Instead, at just about every turn, he either took less money or turned down offers that involved him giving up the majority of the copyright in the work he was producing. It was his steadfast focus on ownership, along with the discipline to turn down immediate fortunes, that allowed him to build the empire and billion-dollar net worth he now has today.

You also have someone like Oprah, the original Black content owner. She was a highly paid talk show host in the mid-80s and could have been content with being just that. But when she began analyzing the deal she signed in 1984, she thought there was much more to be had. So she took the risk of replacing her then “nice” guy, but also record-breaking, agent with a so-called “piranha” of a lawyer who negotiated, in Oprah’s favor, copyrights, lower distribution fees, and ownership stakes in her show. With that as her foundation, the subsequent growth of “The Oprah Winfrey Show” that took place over the next 15 years allowed her to reap more of the benefits than otherwise would’ve happened, enabling her to turn her TV platform into a huge ownership stake in the OWN cable channel, the crown jewel and pinnacle of her business career.

Those are two amazing examples that have led to what are probably the two richest Black people to build their wealth through media. Just imagine if some of the other Black icons in Hollywood and/or media were empowered to take those same risks:

- Spike Lee has grossed over $500 million at the box office but barely owns any of the copyrights to his films. Might he be the “film school” opposition to Tyler Perry had he been able to maintain those rights and put more capital at risk to produce even more amazing Black stories?

- Shonda Rhimes is immensely successful and immensely powerful, having created some of the biggest shows on network and streaming television. Still, as powerful as she is, she doesn’t own any of the popular shows she created for those platforms. Imagine if she had the recurring income stream from those shows that someone like Dick Wolf (Law & Order) was able to negotiate away. We may have entirely new worlds of diverse, unapologetic, female-driven shows being created.

- Malcolm D. Lee created “The Best Man”, which in 1999 was an immediate cultural classic within the Black community, doing just about as well as “Cruel Intentions” in the domestic box office. The latter spawned 2 sequels within 5 years, while “The Best Man” wouldn’t get its first sequel for another 14 years, and its second sequel, as a TV show, The Best Man: The Final Chapters, 23 years later. Had “The Best Man” been owned and distributed by its creator or a Black-run studio, which could’ve better invested in the original movie’s international roll-out, might the franchise have been given the greenlight much earlier?

- Aaron McGruder gave up the rights to “The Boondocks” when he took his comic strip to Adult Swim, but what if he had maintained ownership in that? Would he be the Black version of The South Park creators, which were able to snag away 50% ownership of streaming rights for their show?

- Issa Rae is now one of the most prolific Black actresses and producers in Hollywood, but could the masses have seen her greatness earlier and more frequently had she been able to secure the capital to produce and distribute her many ideas? Might her shows have even been different, or even better, if she hadn’t had to listen to ridiculous comments from white Hollywood executives?

- Donald Glover has proven to be a creative genius. Might his debut creation of “Atlanta” been sooner, longer, more in depth, or dare I say would Atlanta have been even better if Glover was able to own or work with a line of distribution

Why Do Black People Continue To Get Shortchanged

It’s one thing to have had so much racism in Hollywood when it was birthed during Jim Crow, a time in this nation when racial inferiority was an acceptable excuse for anything concerning harming Black people. Yet, here in the 21st century, the relics of Jim Crow are still alive and well in Hollywood, when in theory, they shouldn’t be.

We spoke about Blackface happening in the 1920s, but low and behold, we had “blackvoice” going on right through 2020. It took the death of George Floyd to call to attention to the fact that throughout entertainment, there were many examples of white people voicing animated, Black characters.

Voice acting is one of the best jobs in Hollywood. On a big animated movie or TV series, you can make a full year’s income in just a couple of sessions in the booth. It’s a way for a Black actor or actress to stabilize themselves in the industry and have the financial confidence to take the risks necessary to actually thrive in Hollywood. But when you don’t get the opportunities to play the very few Black animated characters created for television, you’re deprived of the real opportunity of investing in your future. Recent examples of blackvoice include:

- Jenny Slate, a white and Jewish woman, played a half-Black girl named Missy in Big Mouth.

- David Herman, a white man, played a Black transgender sex worker on Bob’s Burgers.

- Hank Azaria, a white man, played several non-white characters, including that of Drederick Tatum, a recurring Black character on The Simpsons.

The list does go on.

As you can imagine, the racial discrimination in Hollywood does not end with animation. UCLA has been studying the effects of race in television and film for quite some time with their Hollywood Diversity Report. In looking at television, the university has found some progress has been made over the years when it comes to proportionally representing Black people on screen; however, the progress is slow and often involves taking 1 step forward and 2 steps back…at best.

For example, when looking at some of UCLA’s recent reports for the 2019-2020 TV season, as well as the 2020-2021 season, Black people are increasingly being fairly represented (volume-wise), and even over-represented in some cases, when it comes to acting roles on cable and digitally scripted TV shows. However, despite progress in front of the camera, the percentage of TV show creators that are Black, Latino or Asian is just a combined 13%.

And in the 2019-2020 season, voted on after George Floyd’s murder, only 1 out of a possible 20 Emmy nominations for Outstanding Comedy, Drama or Limited Series went to a show with a Black creator. Spoiler alert, they did not win. With all of that supposed representation in 2020, one would expect Black creators to fare better when it comes to awards time. So when they don’t, it suggests that when Black people finally do get some modicum of “power” in Hollywood and get to be in and create TV shows, they either aren’t getting the resources and budgets to create amazing shows, or the content they’re “permitted” to make is lacking in the substance worthy of an Emmy.

And sometimes, even when Black creators do get the resources to make something amazing, the rug often gets pulled out from underneath them.

For example, take Misha Green, an immensely talented Black screenwriter, whose “Lovecraft Country” actually did get nominated for Outstanding Drama in 2021, following its inaugural season. Beyond the critical claim, it was a commercial success, as it was one of HBO’s most in-demand series ever. It was so in-demand, that no other series from that same year, having achieved the same level of demand from audiences, would get canceled.

But Misha Green’s series?

Canceled after one season.

The reasoning? It was too expensive to do a second season…of the #1 show on HBOMax at the time! Go figure???

It also probably doesn’t help, as the UCLA study points out, that white people are far less likely to watch a majority Black-casted TV show, as the average ratings among white audiences for an episode of TV with more than 50% of its cast being of a minority race was lower than for the average ratings for shows with lower levels of minority cast members. Furthermore, the data shows there is relatively little chance that the average white viewer will watch a TV show that was written by a predominately Black writers room.

Unfortunately, these numbers are self-fulfilling philosophical atrocities. Hollywood has long argued that because Black shows and movies don’t perform as well in the ratings and box offices, they cannot afford to invest as much in Black programming. Of course, if you don’t invest in something properly and take the requisite risk, you can’t possibly expect a “genre” of programming to do as well as other genres that get more opportunities and more dollars. This underinvestment has led to even someone like Denzel Washington being labeled by the one-time Sony Pictures executives as someone who could not carry an international Blockbuster film. Admittedly, the historical numbers may suggest that is true, but is that because international audiences are “racist”, as they put it…? Or is it because Hollywood has not spent the time nor money marketing Black leads internationally, and thus, there are far fewer Black international movie stars than there should be? It’s that line of thinking and sincere fictions–that Black actors can only carry smaller budget films–that have reduced and constrained Black people in media for well over a century.

To say it another way: Hollywood has failed to take advice from one of its own movies: It has not been willing to bet on Black.

Lots of the studies being done about Black people in Hollywood focus on who is in front of the camera, and sometimes, who is behind the camera. But the UCLA Diversity in Hollywood report did touch on where things are most important: who is in the boardroom? In doing so, it found that 92% of studio executives are white.

Spike Lee touched on this phenomenon in 2016:

“It has to go back to the gatekeepers. The people who have the green-light vote…We’re not in the room. The executives, when they have these green-light meetings, quarterly, where they look at the scripts, they look who’s in it, and they decide what we’re making and what we’re not making.”

Spike lee

As long as Black people are not in the room deciding what Hollywood–the industry with the biggest budgets and the biggest influence on global entertainment–is making, how can we expect Black people to thrive in this industry?

Money is almost everything in Hollywood. The projects with the biggest financial backing and the most distribution generally get the spoils. The power of the purse is real. And if Black creators, directors, studio execs, and actors don’t control the money or the distribution, they are forever going to be beholden to people who may or may not see their work as economically or culturally viable as someone else’s.

What to do in a Post George Floyd World ?

After George Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020, many people in Hollywood made promises that things would change–that more Black representation would come about. Unfortunately, the best studies on Hollywood generally take some time, so I don’t know exactly how many Black TV shows there have been this past year. Based on the UCLA Hollywood Diversity Report, it would appear there were 56 TV shows led by Black people at the end of 2019-2020 TV season. Are we higher than that now? Probably, and as one article from Indiewire would suggest, the number of Black TV shows for the 2021-2022 season was 71. But do I think as a percentage of quality TV that Black TV shows have increased?

Nope. And the 2022 Emmy nominations, in which Black creators got 1 out of a possible 21 nominations for the top 3 awards, would suggests that my presumptions are at least close to being right.

On a positive note, Hollywood has taken down certain types of problematic programming. As I alluded to earlier, the act of blackvoicing may have actually been killed. And a number of policing shows, that tend to over-index in showcasing brutality against Black men, seem to have gotten the boot.

But as previously mentioned, we saw a similar trend in the 60s, when the Civil Rights movement was gaining traction and the media mostly did away with the prevailing racist shows of the time. So history would suggests this current trend is fleeting. The Civil Rights movement led to some changes in Hollywood during the 60s, but as the country’s attention got behind Nixon and the Vietnam War, blaxploitation films became a thing and Black people went most of the 70s and early 80s without seeing themselves represented on TV. And after the peak of Black TV in 1997, we had just 6 Black sitcoms on air in 2001, and we only got back up to 8 Black sitcoms by 2018–in a year in which there were 498 original TV shows released. So yes, we have probably added to the 56 Black-led shows from 2020, at least in part, as a response to George Floyd, but what happens when the “trendiness” of responding to his death fully wears off? Or as America gets ready for a recession? I think we know the answer: Black content will be the first to get the axe. We’re already seeing it. Warner Brothers Discovery, AMC, and even Netflix have made some surprising cuts to Black programming or initiatives all in an effort to save money.

Some may say this time is different as the country has its eyes focused on a date when minorities become the majority in America. But then again, the Black population is relatively steady as a percentage of the population, having actually fallen from 12.6% of the population in 2010 to 12.4% in 2020. Meanwhile, Latinos continue to grow in numbers–in absolution and as a percentage of the country. From an economic perspective, it’s very logical that Hollywood would turn its focus toward a bigger, and potentially more economically-advantageous, Latino population that has also been seriously disrespected.

How Do We Buck The Trend?

The only way to assure that Black content is here to stay is for Black people to take the risk and make it so. The most American thing to do in this country is to bet on yourself. It’s time that we as Black consumers bet on our content. Our stories. Our imaginations. We cannot rely on the system as it is to fully invest in our visions if they do not share those same visions with us. A Sony executive who cannot foresee a global audience for Denzel Washington will never bet on Denzel. But a Black executive, free to make their own decisions, and beholden to no one but the Black viewer, will make the content that Black viewers want to see–and that almost assuredly means LOTS of Mr. Washington.

What Oprah, Tyler Perry, and Shonda Rhimes have built is beautiful. They are making lots of great content that lots of Black people consume every day–and we are better for it. But why is that they’re not able to produce something with the budget of a Game of Thrones, Stranger Things, or even a mediocre, but extremely pricey, show like The Morning Show from AppleTV+? Of the 11 most expensive shows ever made, none of them were by Black creators. Pretty sure the same goes for the 25 most expensive shows. Of course, this is not because Black creators don’t have the creative talent or ambition to make such sprawling stories. It’s because…

Ownership.

Yes, Tyler Perry owns just about everything he touches. And Oprah is perhaps the richest Black woman in America. Yet, neither of them has ever has had the opportunity to create something as expansive or daring (i.e., expensive) as the shows on those “most expensive” lists. And while sometimes they do own their content, what never own is the distribution or the financial infrastructure. It’s reported that Tyler Perry can make any production he wants to as part of his deal with Viacom and BET, and while that may be true, he certainly can’t ask for any budget that he wants to have to make said production. Oprah may have her own network, but if enough advertising dollars aren’t going to support her desire to reboot the critically acclaimed “Underground” series, then that show doesn’t get to go on. Even Michaela Coel’s turning down a better financial offer from Netflix because they wouldn’t give her a slice of the copyright for “I May Destroy You“, while definitely a step in the right direction and immensely applauded by me, isn’t enough to buck the system. Netflix is still doing (relatively) well.

Perhaps, in the grand scheme of things, these Black titans of the media industry have a strategic plan to negate the ills I’ve spoken of. But as it stands, those Black leaders–along with other amazing creators like Shonda Rhimes and Ava Duvernay–see most, if not all, of their income derived from the Hollywood Industrial Complex. The same complex where 92% of the executives are White.

Yeah, we don’t own that complex.

And I don’t know if one can successfully navigate a path forward for the collective progression of Black content within a complex someone else owns. So while the individual success of Black content creators is something I’m proud to acknowledge every day, I don’t get too excited thinking that we are going to make Hollywood make a true pivot to giving Black creators (and viewers) a fair stake in this industry.

What does have me excited though?

It’s that the whole damn system is crumbling.

A one-time vacuum cleaner salesman from Boston and a Video Store Executive are the most important people in entertainment and spend more money on scripted content than anybody else–all because of the internet.

WarnerMedia (now Warner Bros. Discovery) set fire to its relationships with the theaters during the pandemic, and perhaps, with the entire power structure in Hollywood.

Disney risked reputation, leadership, and the threat of a civil lawsuit, to release a proven franchise on the internet because…streaming.

A site where teenage girls can learn physics, and pre-pubescent boys stream video games, gets more video viewing hours than any other singular media brand in the world.

And to add insult to injury, all of the companies I just mentioned, their stock prices are plummeting. Yeah, the macro environment sucks, but truth be told, so does the current state of their unit economics.

Simply put, the walls are falling in on Hollywood.

But like most falling industries, it doesn’t mean they’ll try to change the foundation–they’re going to tape this bad boy up and try to make it work. Post-pandemic, we now have people saying movie theaters are back, sports rights fees are soaring, and the Oscars weren’t that white, but the Emmys were.

Thankfully, you can’t really stop falling walls, and you can’t control who gets to resurrect them either. So it’s not just the Netflixes and YouTubes of the world that are going to get to have a say in the future of Black people in media. This is a time when Black people can stop asking to be on shows and create their own. This is a time when instead of taking whatever role we can get, we can play all of the roles. This is a time when if our community needs reporting, we can pick up a damn camera and broadcast it to the world.

Hollywood’s original sin wasn’t a racist trope or a separate table at an award show. Its original sin was the systemic removal of Black people in Hollywood from the American dream: allowing people to risk it all and bet on themselves.

And for over a century, the data shows Hollywood has largely not afforded Black people the equity, access, influence, nor the capital to take our own risks and tell our own stories. We got no say. We got no vote. We got no representation in Hollywood’s boardrooms. But now, because of the opportunity technology has afforded us, and because try as they might, Hollywood cannot own the internet, it’s now time for Black people to correct for this sinful transgression, especially when atonement is near an all-time high.

But we’ll have to take what’s ours.

That means saying no to some things that feel good. And it means saying yes to things that are risky. Because it is only by taking risks, like Issa Rae’s with Hoorae, Byron Allen’s with Entertainment Studios, or even mine with BlackOakTV, that we will get equity in the future of Hollywood. If you need proof of that, just ask the racist producers who created it way back in 1915.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.